About trout and other sweet and salt water fish. // Sobre truchas y otros peces y pescados de agua dulce y salada.

ATOLE CON EL DEDO

(*Texto en español, abajo.)

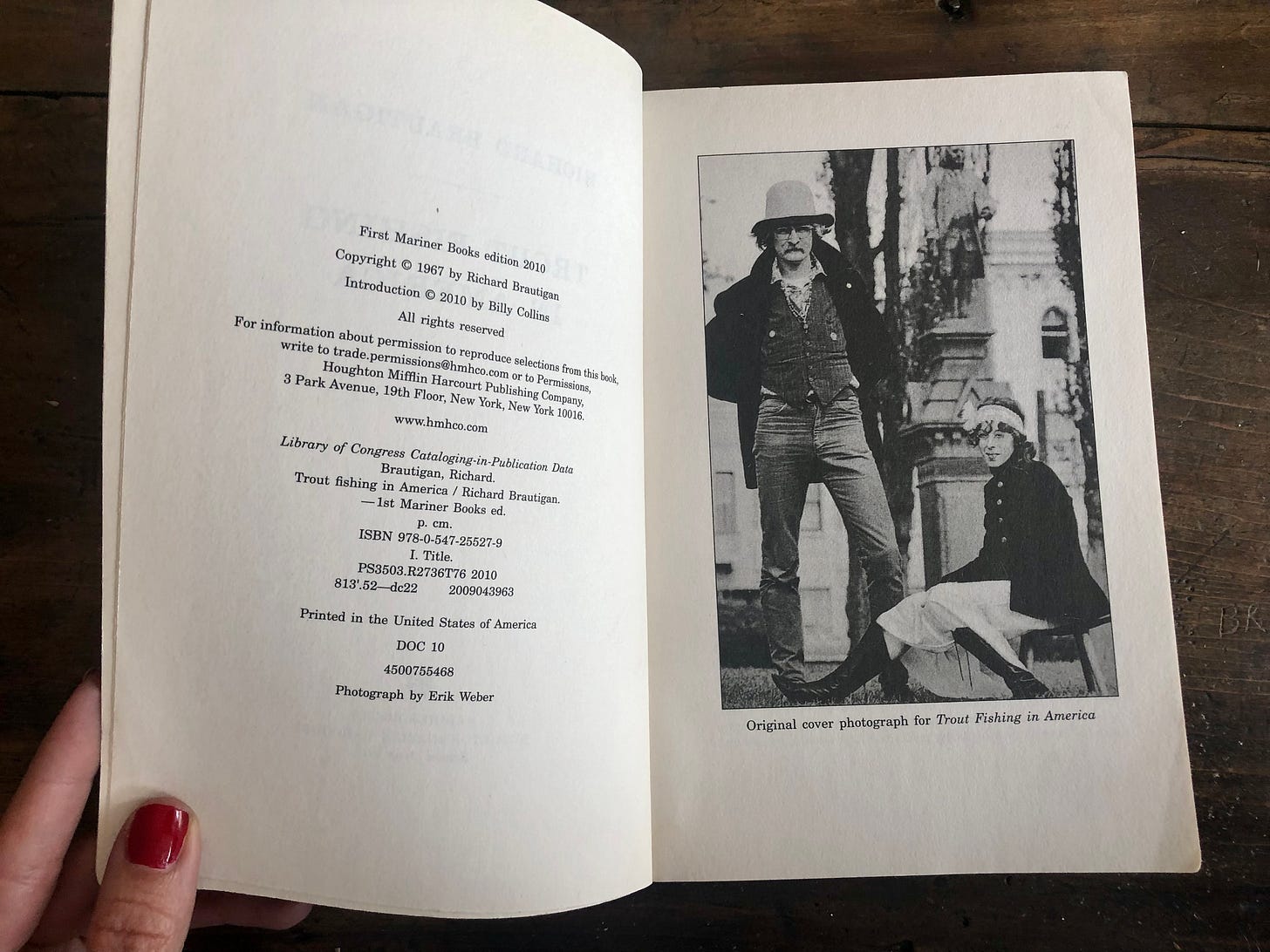

This is an excerpt from the book Trout Fishing in America, by Richard Brautigan.

*To view a gallery with the whole selection of artwork in this post go to my lists.

Richard Brautigan (1935–1984) was an American writer, popular in the 60's and 70's, novelist, poet and short story writer, iconoclast, late member of the Beat Generation. In addition to Trout Fishing in America (1967), two of his best known works are: In Watermelon Sugar (1968), and The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966 (1971).

TROUT DEATH BY PORT WINE

It was not an outhouse resting upon the imagination.

It was reality.

An eleven-inch rainbow trout was killed. Its life taken forever from the waters of the earth, by giving it a drink of port wine.

It is against the natural order of death for a trout to die by having a drink of port wine.

It is all right for a trout to have its neck broken by a fisherman and then to be tossed into the creel or for a trout to die from a fungus that crawls like sugar-colored ants over its body until the trout is in death’s sugarbowl.

It is all right for a trout to be trapped in a pool that dries up in the late summer or to be caught in the talons of a bird or the claws of an animal.

Yes, it is even all right for a trout to be killed by pollution, to die in the river of suffocating human excrement.

There are trout that die of old age and their white beards flow to the sea.

All these things are in the natural order of death, but for a trout to die from a drink of port wine, that is another thing.

No mention of it in “The treatyse of fysshynge with an angle,” in the Boke of St. Albans, published in 1496. No mention of it in Minor Tactics of the Chalk Stream, by H. C. Cutcliffe, published in 1910. No mention of it in Truth is Stranger than Fishin’, by Beatrice Cook, published in 1955. No mention of it in Northern Memoirs, by Richard Franck, published in 1694. No mention of it in I Go A-Fishing, by W. C. Prime, published in 1873. No mention of it in Trout Fishing and Trout Flies, by Jim Quick, published in 1957. No mention of it in Certaine Experiments Concerning Fish and Fruite, by John Taverne, published in 1600. No mention of it in A River Never Sleeps, by Roderick L. Haig-Brown, published in 1946. No mention of it in Till Fish Us Do Part, by Beatrice Cook, published in 1949. No mention of it in The Flyfisher and the Trout’s Point of View, by Col E. W. Harding, published in 1931. No mention of it in Chalk Stream Studies, by Charles Kingsley, published in 1859. No mention of it in Trout Madness, by Robert Traver, Published in 1960.

No mention of it in Sunshine of the Dry Fly, by J. W. Dunne, published in 1924. No mention of it in Just Fishing, by Ray Bergman, published in 1932. No mention of it in Matching the Hatch, by Ernest G. Schwiebert, Jr., published in 1955. No mention of it in The Art of Trout Fishing on Rapid Streams, by H. C. Cutcliff, published in 1863. No mention of it in Old Flies in New Dresses, by C. E. Walker, published in 1898. No mention of it in Fisherman’s Spring, by Roderick L. Haig-Brown, published in 1951. No mention of it in The Determined Angler and the Brook Trout, by Charles Bradford in 1916. No mention of it in Women Can Fish, by Chisie Farrington, published in 1951. No mention of it in Tales of the Angler’s El Dorado New Zealand, by Zane Grey, published in 1926. No mention of it in The Flyfisher’s Guide, by G. C. Brainbridge, published in 1816.

There’s no mention of a trout dying by having a drink of port wine anywhere.

To describe the Supreme Executioner: We woke up in the morning and it was dark outside. He came kind of smiling to the kitchen and we ate breakfast.

Fried potatoes and eggs and coffee.

“Well, you old bastard,” he said. “Pass the salt.”

The tackle was already in the car, so we just got in and drove away. Beginning at the first light of dawn, we hit the road at the bottom of the mountains and drove up into the dawn.

The light behind the trees was like going into a gradual and strange department store.

“That was a good-looking girl last night,” he said.

“Yeah,” I said. “You did all right.”

“If the shoe fits…” he said.

Owl Snuff Creek was just a small creek, only a few miles long, but there was some nice trout in it. We got out of the car and walked a quarter of a mile down the mountainside to the creek. I put my tackle together. He pulled out a pint of port wine out of his jacket pocket and said, “Wouldn’t you know.” “No, thanks,” I said.

He took a good snort and then shook his head, side to side, and said, “Do you know what this creek reminds me of?” “No,” I said, tying a gray and yellow fly onto my leader.

“It reminds me of Evangeline’s vagina, a constant dream of my childhood and a promoter of my youth.”

“That’s nice,” I said.

“Longfellow was the Henry Miller of my childhood,” he said.

“Good,” I said.

I cast into a little pool that had a swirl of fir needles growing around the edge of it. The fir needles went around and around. It made no sense that they should come from the trees. They looked perfectly contented and natural in the pool as if the pool had grown then on watery branches.

I had a good hit in my third cast, but missed it.

“Oh boy,” he said. “I think I’ll watch you fish. The stolen painting is in the house next-door.”

I fished upstream coming ever closer and closer to the narrow staircase of the canyon. Then I went up into it as if I was walking entering a department store. I caught three trout in the lost and found department. He didn’t even put his tackle together. He just followed after me, drinking por wine and poking a stick to the world.

“This is a beautiful creek,” he said. “It reminds me of Evangeline’s hearing aid.”

We ended up at a large pool that was formed by the creek, crashing through the Children’s toy section. At the beginning of the pool the water was like cream, then It mirrored out and reflected the shadow of a large tree. By this time the sun was up. You could see it coming down the mountain. I cast into the cream and left my fly drift down onto a long branch of a tree, next to a bird.

Go-wham!

I set the hook and the trout started jumping.

“Giraffe races at Kilimanjaro!” he shouted, and every time the trout jumped, he jumped.

“Be races at Mount Everest!” he shouted.

I didn’t have a net with me so I fought the trout over to the edge of the creek and swung it up onto the shore.

The trout had a big red stripe down its side.

It was a good rainbow.

“What a beauty,” he said.

He picked it up and it was squirming in his hands.

“Break its neck,” I said.

“I have a better idea,” he said. “Before I kill it, let me at least soothe its approach to death. This trout needs a drink.” He took the bottle of port out of his pocket, unscrewed the cap and poured a good slug into the trout’s mouth.

The trout went into a spasm.

Its body shook very rapidly like a telescope during an earthquake. The mouth was wide opened and chattering almost as if it had human teeth. He laid the trout on a white rock, head down, and some of the wine trickled out of his mouth and made a stain on the rock.

The trout was lying very still now.

“It died happy,” he said.

“This is my ode to Alcoholics Anonymous.”

“Look here!”

Sección en español.

Este es un extracto del libro Trout Fishing in America, de Richard Brautigan.

(*Para ver una galería con toda la selección de obras de arte en esta publicación, vayan a mis listas.)

Richard Brautigan (1935–1984) fue un escritor norteamericano, popular en los 60’s y 70’s, novelista, poeta y cuentista, iconoclasta, miembro tardío de la Generación beat. Además de Trout Fishing in America (1967), dos de sus obras más conocidas son: In Watermelon Sugar (1968), and The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966 (1971).

MUERTE DE TRUCHA POR VINO DE OPORTO

No era una letrina descansando sobre la imaginación.

Era la realidad.

Una trucha arco iris de once pulgadas fue asesinada. Su vida arrebatada para siempre de las aguas de la tierra, por un trago de oporto.

Va contra el orden natural de la muerte que una trucha muera tomando un trago de oporto.

Está bien que un pescador le rompa el cuello a una trucha y luego la arroje a la cesta o que una trucha muera a causa de un hongo que repta como hormigas color azúcar sobre su cuerpo hasta que la trucha está en el azucarero de la muerte.

Está bien que una trucha quede atrapada en un estanque que se seca a fines del verano o que quede atrapada en las garras de un ave o en las garras de un animal.

Sí, incluso está bien que una trucha muera por la contaminación, que muera en un río de excrementos humanos sofocantes.

Hay truchas que se mueren de viejas y sus barbas blancas fluyen hacia el mar.

Todas estas cosas están en el orden natural de la muerte, pero que una trucha muera por un trago de oporto, eso es otra cosa.

No se menciona en "El treatyse de fysshynge con caña", en el Boke de St. Albans, publicado en 1496. No se menciona en Tácticas menores del arroyo calizo, de H. C. Cutcliffe, publicado en 1910. No se menciona en La verdad es más extraña que la pesca, de Beatrice Cook, publicado en 1955. No se menciona en Memorias del Norte, de Richard Franck, publicado en 1694. No se menciona en I Go A-Fishing, de W. C. Prime, publicado en 1873. No se menciona en Pesca de trucha y moscas de trucha, de Jim Quick, publicado en 1957. No se menciona en Certaine experiments sobre pescado y fruite, de John Taverne, publicado en 1600. No se menciona en Un río nunca duerme, por Roderick L. Haig-Brown, publicado en 1946. No se menciona en Hasta que el pescado separe nos, de Beatrice Cook, publicado en 1949. No se menciona en El pescador con mosca y el punto de vista de la trucha, por Col E. W. Harding, publicado en 1931. No se menciona en Estudios sobre arroyos calizos, de Charles Kingsley, publicado en 1859. No se menciona en Locos por la trucha, de Robert Traver, publicado en 1960.

No se menciona en Resplandor de la mosca seca, de J. W. Dunne, publicado en 1924. No se menciona en Sólo pesca, de Ray Bergman, publicado en 1932. No se menciona en Igualando la trampa, de Ernest G. Schwiebert, Jr., publicado en 1955. No se menciona en El arte de pescar trucha en los rápidos, de H. C. Cutcliff, publicado en 1863. No se menciona en Moscas viejas en vestidos nuevos, de C. E. Walker, publicado en 1898. No se menciona en El manantial de pescador, de Roderick L. Haig-Brown, publicado en 1951. No se menciona en El mosquero determinado y la trucha boke, de Charles Bradford en 1916. No se menciona en Las mujeres pueden pescar, de Chisie Farrington, publicado en 1951. No se menciona en Historias de El Dorado Nueva Zelanda del pescador, de Zane Grey, publicado en 1926. No se menciona en La guía del pescador con mosca, de G. C. Brainbridge, publicado en 1816.

No se menciona que una trucha haya muerto a causa de un trago de oporto en ninguna parte.

Para describir al Verdugo Supremo: Nos despertamos por la mañana y estaba oscuro afuera. Llegó algo sonriente a la cocina y desayunamos.

Patatas fritas y huevos y café.

"Bueno, viejo bastardo", dijo. "Pasa la sal."

Las cañas ya estaban en el auto, así que nos subimos y nos fuimos. Comenzando con las primeras luces del amanecer, salimos a la carretera al pie de las montañas y nos dirigimos hacia el amanecer.

La luz detrás de los árboles era como entrar en una gradual y extraña tienda departamental.

“Era guapa la chica de anoche”, dijo.

"Sí", dije. Lo hiciste bien.

“Si el zapato calza…”, dijo.

Owl Snuff Creek era solo un pequeño arroyo, a unas pocas millas de distancia, pero había muy buenas truchas. Salimos del auto y caminamos un cuarto de milla por la ladera de la montaña hasta el arroyo. Preparé mi caña. Sacó una pinta de vino de oporto del bolsillo de su chaqueta y dijo: "¿Cómo saberlo?". “No, gracias”, dije.

Dio un buena aspirada y luego sacudió la cabeza, de lado a lado, y dijo: "¿Sabes a qué me recuerda este arroyo?" “No,” dije mientras ataba una mosca gris y amarilla a mi caña.

“Me recuerda a la vagina de Evangeline, un sueño constante de mi infancia y un promotor de mi juventud”.

"Eso es bueno", dije.

“Longfellow fue el Henry Miller de mi infancia”, dijo.

“Bien,” dije.

Lancé a un pequeño charco que tenía un remolino de agujas de abeto creciendo alrededor del borde. Las agujas de abeto dieron vueltas y vueltas. No tenía sentido que vinieran de los árboles. Se veían perfectamente contentas y naturales en la piscina, como si la piscina hubiera crecido sobre ramas acuosas.

Tuve un buen golpe en mi tercer lanzamiento, pero fallé.

"Vaya chico", dijo. “Creo que te veré pescar. El cuadro robado está en la casa de al lado.

Pesqué río arriba acercándome cada vez más a la estrecha escalera del cañón. Luego me subí a él como si estuviera entrando a una tienda por departamental. Atrapé tres truchas en el departamento de cosas perdidas. Ni siquiera preparó su caña. Simplemente me siguió, bebiendo oporto y pinchando el mundo con un palo.

“Este arroyo es hermoso”, dijo. “Me recuerda al aparato para la sordera de Evangeline”.

Terminamos en una gran piscina que formaba por el arroyo, desbordándose através de la de la jugetería. Al comienzo de la piscina, el agua era como crema, luego se convertía en espejo y reflejaba la sombra de un gran árbol. En ese momento el sol estaba en lo alto. Se podía ver bajando de la montaña. Me lancé a la crema y dejé que mi mosca flotara sobre la rama larga de un árbol, junto a un ave.

¡Vaya!

Coloqué el anzuelo y la trucha empezó a saltar.

“¡Carreras de jirafas en el Kilimanjaro!” gritó, y cada vez que saltaba la trucha, él saltaba también.

“¡Carreras en el Monte Everest!” gritó.

No tenía una red conmigo, así que peleé con la trucha hasta el borde del arroyo y la aventé a la orilla.

La trucha tenía una gran franja roja en el costado.

Era un buen arcoíris.

“Qué belleza”, dijo.

La recogió y se retorcía entre sus manos.

“Tuércele cuello”, dije.

"Tengo una mejor idea", dijo. “Antes de matarla, déjame al menos aliviar su aproximación a la muerte. Esta trucha necesita un trago. Sacó la botella de oporto del bolsillo, desenroscó el tapón y vertió un buen trago en la boca de la trucha.

La trucha entró en un espasmo.

Su cuerpo se sacudió rápidamente como un telescopio durante un terremoto. Tenia la boca estaba abierta de par en par y castañeteaba casi como si tuviera dientes humanos. Puso a la trucha sobre una roca blanca, con la cabeza hacia abajo, unas gotas de vino se derramaron de su boca y manchó la roca.

Ahora, la trucha yacía quieta.

“Murió feliz”, dijo.

“Esta es mi oda a Alcohólicos Anónimos”.

"¡Miren aquí!"